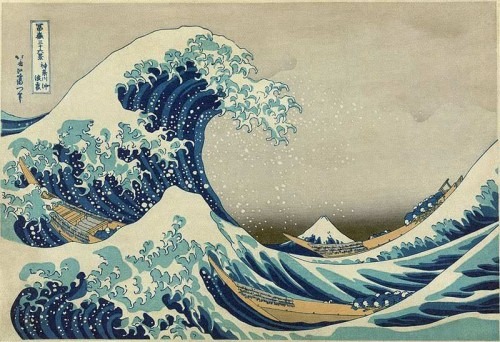

She looks as if she is about to be overwhelmed by a giant tidal wave, just like the fishermen in Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa

Before the advent of monotheistic religions peoples of antiquity held that gods resided in places and that their voices holding eternal truths could be heard if you only listened – what the Romans referred to as Genius Loci. In Europe this belief persisted in country districts until recent times. The Genius Loci is not just a spirit in the place but the spirit of the place.

In Japan the early 19th century artist Hokusai, a man who created his best work after sixty, believed in the Genius Loci, not so much of a place but a mountain – Fuji. The mountain had been considered sacred for millennia before him, but the Buddhist artist came to believe as he aged that Fuji held a secret: the key to immortality, the very etymology means “not-death”. Aged 70 he embarked on a series of forty-six prints of views of Mount Fuji (this contains the famous “Great Wave off Kanagawa’) then at 75 he published a book, ‘One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji’. By courting the mountain he believed that he could not only extend his own life, but that the resulting marriage would render him immortal.

Great Wave off Kanagawa (1832) Hokusai

In a celebrated declaration of wishful thinking he described his life up to seventy-five thus:

From around the age of six, I had a penchant for sketching from life. I became an artist, and from fifty on began producing works that won some reputation, but nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention. At seventy-three, I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects and fish, and of the way plants grow. If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one hundred and thirty, forty, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive. May Heaven, that grants long life, give me the chance to prove that this is no lie.

I know of a place called Vulci, a former Etruscan city but also a deep gorge in which the cliffs arch over the ravine in a fabulous petrified wave of stalactites. Samara and I plus assistant Liz, trekked up the Vulci gorge to find the perfect spot under the cliffs. Slippery rocks, rapids, wading through the river and then climbing over sharp stalagmites up the cliff itself – it really was a trek, and all this Samara did fully made up with a turban and veil! What is more the sound of the rushing water made communication well nigh impossible. But how beautiful she looked perched on her eyrie half veiled under the arching wave of stalactites. The cliff is dramatically beautiful, it is the sort of place you want to burst out singing, yet even though the figure is so tiny and the breaking wave of the cliff dwarfs her, would the landscape be half so beautiful without her presence? She is the spirit of the place, the Genius Loci.

And beauty, like art is not easy to pin down. Samara talked to me of Gibran and in his poem On Beauty he describes how people see beauty as a need that needs satisfying, rather he says,

….. beauty is not a need but an ecstasy.

It is not a mouth thirsting nor an empty hand stretched forth,

But rather a heart enflamed and a soul enchanted.

Hokusai returned to the great wave theme in his ‘One Hundred Views of Fuji’. This time however the wave is not threatening, there is a oneness in nature, the birds and the crest of the wave are in harmony. A harmony I like to think is to be found here in the image of Samara under the mountainous wave.

Beauty is life when life unveils her holy face.

But you are life and you are the veil.

Beauty is eternity gazing at itself in a mirror.

But you are eternity and you are the mirror.

(Gibran, On Beauty)

I wonder if Gibran appeals especially to Samara because the man and his poetry bridge two cultures, perhaps both of them dreaming in Arabic and writing in English? The Christian Gibran who like Christ himself was acquainted with grief, appeals across religious and cultural divides, his poetry arches over bigotry and dogma. Truth is eternal, beauty is rendered immortal, the Genius Loci holds the key to eternity.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

(Shakespeare, Sonnet 18)

Hokusai died prematurely at 89, Gibran at 48, Shakespeare at 52; all are immortal…….and they know it