Metamorphoses

Arbor Vitae

The inscription on Arbor Vitae was done by a female Japanese student who chanced upon my Orvieto gallery one day. I asked her if she could write some Japanese calligraphy, anything as long as it was beautiful. She wrote in silver ink directly on the print, “Even a chance encounter is part of our destiny.” I was so moved that I have used it on the frontispiece of my book Belle, on my business card and elsewhere.

The most famous Metamorphoses are those written by the Latin poet Ovid illustrating Greek myths and a source for countless artists, poets, painters and sculptors. Bernini based his statue Apollo and Daphne on Ovid’s tale and I was in turn inspired by Bernini. However, for the rest of the series I was more inspired by music than poetry or painting: Richard Strauss’ Metamorphosen.

After the destruction of Munich Opera House by allied bombing in 1944, Richard Strauss sought atonement in composition and consolation in poetry: it was Goethe’s Metamorphosis of Plants that inspired the heartbreaking melancholy of Metamorphosen, sonata for 23 strings.

“Plastic and forming, may man change e’en the figure decreed!

Oh, then, bethink thee, as well, how out of the germ of acquaintance,

Kindly intercourse sprang, slowly unfolding its leaves;

Soon how friendship with might unveil’d itself in our bosoms,

And how Amor, at length, brought forth blossom and fruit

Think of the manifold ways wherein Nature hath lent to our feelings,

Silently giving them birth, either the first or the last!

Yes, and rejoice in the present day! For love that is holy

Seeketh the noblest of fruits,–that where the thoughts are the same,

Where the opinions agree,–that the pair may, in rapt contemplation,

Lovingly blend into one,–find the more excellent world.”

Daphne

In a world gone mad, Strauss turns the optimism of Goethe’s world upside down. His pain at the physical destruction, his guilt over his erstwhile support of the Nazis and horror at the destiny of the Jews (his much loved Jewish daughter-in-law thankfully survived) led him to feel that Goethe’s belief in striving for self knowledge as the key to evolution had brought about unprecedented barbarity.

Goethe’s hope that penetration to the core of oneself would lead to a metamorphosis through the discovery of the divine within is not shared by Strauss in the very winter of German culture.

But despite his despair, the very composition of Metamorphosen was part of the transfiguration of the German soul.

It may have been composed in the depth of winter, but when he conducted the dress rehearsal in January 1946, a new world was dawning.

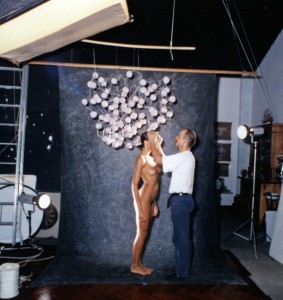

Bevignani makes an adjustment to Pomona

Sylvia

More from this series on my web site.