Plume Fatale – 2009

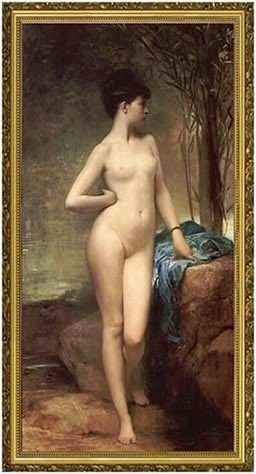

The painting Chloe, which could be the most famous artwork in Australia, hangs not in a gallery or private collection but, unusually for a work of art, in a Melbourne pub, Young and Jackson’s. The Parisian model, Marie, committed suicide after a tragic love affair aged only 21. After a rapturous reception at the Paris Salon where Chloe won a gold medal for Lefebvre, the painting was imported into Australia in I879, but she had trouble finding a home – every time she was exhibited scandal erupted.

Sold in 1908 for less than she had cost in Paris to an antipodean pub could have been considered an ignominious end for Chloe, but in her new home behind the bar she proved to be a positive attraction. She has since been admired by thousands of servicemen, Anzacs, on their way to the front since the First World War on, and no doubt for many a young man Chloe was the first and possibly last view of a naked woman.

In fact in an age when most young men had only the vaguest idea of what a naked woman looked like, Chloe must have been a revelation and one hopes appeared in their dreams as a beautiful night visitor to relieve the daily horrors.

In WW I all Australian servicemen were volunteers, but some were less willing than others and the white feather was handed by women across the Empire to men not in uniform, the plume fatale of this picture.

Jokes were made about over enthusiastic white feather waving ladies:

Young woman to farm-labourer milking a cow, “I say young man, why aren’t you up at the front ?!”

Farm labourer, “Because there ain’t no milk up that end ma’am.”

But to receive a white feather was humiliating,….and persuasive. As the song goes: ‘We don’t want to lose you but we think you ought to go, good bye-ee”.

How would young Jack have felt on reading the following in the Personal Column of The Times? “Jack F.G. If you are not in khaki by the 20th I shall cut you dead. Ethel M.”

So thousands of Jacks, more coerced than persuaded, went off to war with this cheery ditty from 1915 ,’Goodbyeee’ ringing in their ears,

“Wipe the tear, baby dear, from your eye-ee,

Tho’ it’s hard to part I know,

I’ll be tickled to death to go.”

It was not just women who encouraged their menfolk towards the front, but the great, the good and the famous lent their weight to the propaganda: Thomas Hardy, John Galsworthy, Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling, the last two lost their only sons. Kipling wrote a heartbroken mea culpa in 1918,

“If any question why we died.

Tell them, because our fathers lied.”

18 year old Jack Kipling’s body was never found. Conan Doyle in his grief turned to spiritualism.

The framed photo on Chloe’s table is of Lt Percy H Cherry V.C. of Perth, an uncommonly brave man from Western Australia, who could well have caught a glimpse of Chloe on his way to Gallipoli in 1915. He was killed by a shell in France in 1917. Chloe stands newly bereaved in the gloaming, the dreaded pink telegram at her feet.

Wilfred Owen put it best in “Anthem for Doomed Youth”

“The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.”

He too was killed, in France, November 1918, the last week of the war.