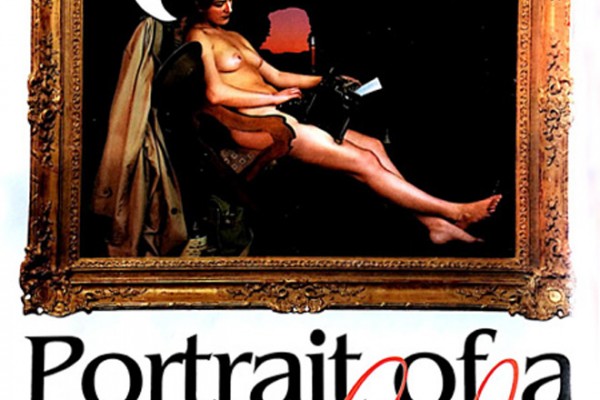

My first version of Ingres’ Odalisque, Casalisca from 1989 published later in The Sunday Times

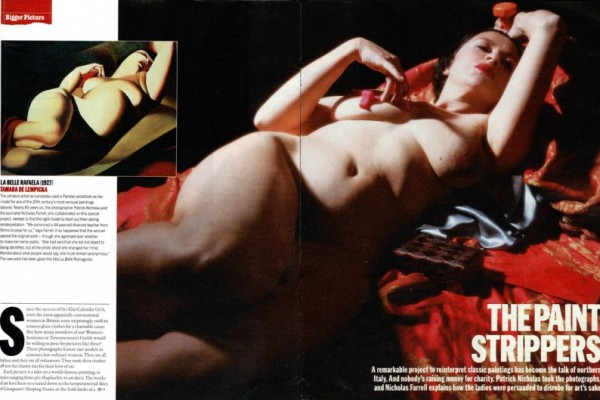

The art-deco artist de Lempicka used ‘a Parisian prostitute as her model for one of the 20th century’s most sensual paintings.

Nearly 80 years on, the photographer Patrick Nicholas and the journalist Nicholas Farrell, who collaborated on this special project, needed to find the right model to flesh out their daring reinterpretation.

“We convinced a 44-year-old divorced teacher from Rimini to pose for us,” says Farrell. It so happened that the woman adored the original work — though she agonised over whether to make her name public. “She had said that she did not object to being identified, but at the photo shoot she changed her mind. Worried about what people would say, she must remain anonymous.” The new work has been given the title La Belle Romagnola.

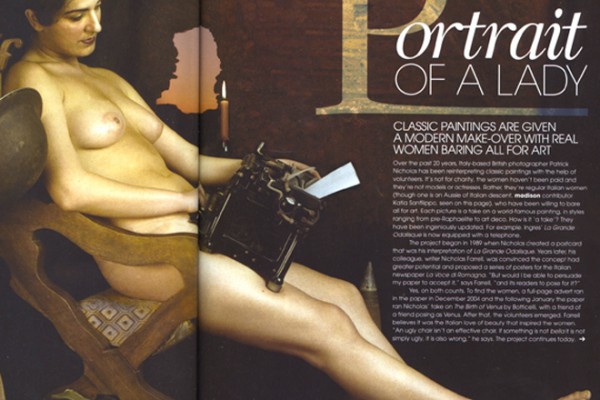

Since the success of the film Calendar Girls, even the most apparently conventional women in Britain seem surprisingly swift to remove their clothes for a charitable cause. But how many members of our Women’s Institutes or Townswomen’s Guilds would be willing to pose for pictures like these? These photographs feature not models or actresses, but ordinary women.

They are all Italian, and they are all volunteers. They took their clothes off not for charity but for their love of art.

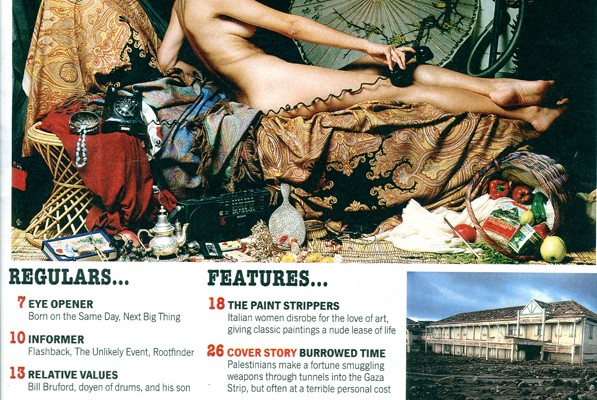

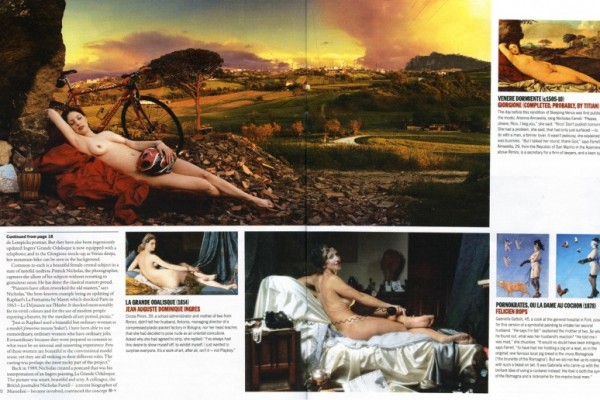

Each picture is a take on a world-famous painting, in styles ranging from pre-Raphaelite to art deco. The works of art have been re-created down to the temperamental skies of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus, or the bold daubs of a de Lempicka portrait. But they have also been ingeniously updated: Ingres’ Grande Odalisque is now equipped with a telephone; and in the Giorgione mock-up, as Venus sleeps, her mountain bike can be seen in the background.

Common to each is a beautiful female central subject in a state of tasteful undress. Patrick Nicholas, the photographer, captures the allure of his subjects without resorting to gratuitous smut. He has done the classical masters proud. “Painters have often reworked the old masters,” says Nicholas, “the best-known example being an updating of Raphael’s La Fornarina by Manet which shocked Paris in 1863 – Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. It shocked most notably for its vivid colours and for the use of modern people enjoying a bizarre, by the standards of any period, picnic.”

“Just as Raphael used a beautiful but ordinary woman as a model (fornarina means ‘baker’), I have been able to use extraordinary, ordinary women who have ordinary jobs. Extraordinary because they were prepared to commit to what must be an unusual and unnerving experience. Few of these women are beautiful in the conventional model sense, yet they are all striking in their different roles. The casting was perhaps the most tricky part of the project.”

Back in 1989, Nicholas created a postcard that was his interpretation of an Ingres painting, La Grande Odalisque. The picture was smart, beautiful and sexy. A colleague, the British journalist Nicholas Farrell — a recent biographer of Mussolini – became involved, convinced the concept had greater potential: “It was my idea to turn it into a series of weekly posters wrapped around the newspaper I write for, La Voce di Romagna. But would I be able to persuade my paper to accept it — and its readers to pose for it?”

Farrell went to Gianni Celli, the owner of La Voce di Romagna, a regional daily paper in the Romagna area of northern Italy, now part of the larger Emilia-Romagna region, which includes Bologna and Rimini. He saw the potential immediately. Full nudity was out of the question but — even so — finding the women was going to be a huge problem, especially as they were not to be paid. Money would debase the project: the women should be volunteers, committed to the idea. They also decided the women had to be Romagnola. But, if a woman could not use money as justification for taking off her clothes and having the results published in a newspaper, then why would she agree?

To find such women, Celli and Farrell ran a full-page advert in the paper, showing Nicholas’s take on The Birth of Venus by Botticelli, with a friend of a friend as Venus. They soon had their volunteer. Farrell thinks this might be because they are Romagnola women. “The Romagna has always had a fiercely independent history. The Romagnoli, of both sexes, have a reputation for being great fun.”

Ultimately, he believes the Italian love of beauty inspired the women. Beauty, Farrell says, is seen as an integral part of function. “An ugly chair isn’t an effective chair. If something is not bella it is not simply ugly; it is also wrong.”